178 – Nurture: a Blackhall Tale, Part 1 of 3

Welcome to Flash Pulp, episode one hundred and seventy-eight.

![]()

Tonight we present, Nurture: a Blackhall Tale, Part 1 of 3.

(Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3)

[audio:http://traffic.libsyn.com/skinner/FlashPulp178.mp3]Download MP3

(RSS / iTunes)

This week’s episodes are brought to you by Words with Walter.

Flash Pulp is an experiment in broadcasting fresh pulp stories in the modern age – three to ten minutes of fiction brought to you Monday, Wednesday and Friday evenings.

Tonight, Thomas Blackhall, master frontiersman and student of the occult, finds himself amidst a wasteland.

Flash Pulp 178 – Nurture: a Blackhall Tale, Part 1 of 3

Written by J.R.D. Skinner

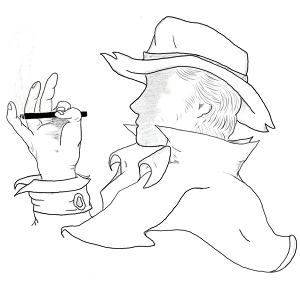

Art and Narration by Opopanax

and Audio produced by Jessica May

Thomas wiped his soot-dirtied palm across the hem of his greatcoat, and promised himself time for proper laundry should he ever again encounter the water necessary.

Thomas wiped his soot-dirtied palm across the hem of his greatcoat, and promised himself time for proper laundry should he ever again encounter the water necessary.

The frontiersman stood on a blackened plain, with a dry mouth and skin cracked from recent heat. He craved the leafy shade that the field of smoking stumps had once represented, but, more over, he longed to return to the journey which would bring him to his Mairi, and away from his current miserable chase – given his thirst, he wasn’t confident he’d live to see its end.

He’d been on the hunt for Silence Babb, and the damnable bairn, for half-a-fortnight, and, while the course was at first relatively simple, the ocean of flame which had risen up amongst the mid-Summer’s timber had, on the fourth evening, and for the full day following, entrapped him in a creek barely wider than his own shoulders.

His escape from the blaze was a near thing.

As he’d readied for his departure from the stream that was his haven, he’d had little idea that it might be his last sight of cool moisture. Almost worse was the fact that, although he could guess the general direction of the traveling-pair, the fire had consumed any marker indicating their actual passage.

Now, as his boots churned up ash and an occasional smouldering ember, he cursed his heart as a fool’s for ever having been sidetracked from the path of his beloved.

The temptation to strip off garments, and leave behind his tools, was strong under the added weight of the noon-sun, but, as he crested yet another cindered hillock, a minuscule buzzing reached his ears.

With a smile, he slapped at the mosquito which alighted upon his cheek.

* * *

Seven days earlier, Thomas had determined that none in Saltflat Township could account for the babe that the woman had carried into the midst of the hardscrabble residents.

Those who’d witnessed her wandering could find no good to say in regards to the lineage of the child, and all were quick to point to the chronic moral degeneracy so often attributed to the family as a whole. Despite their tales of faulty ancestry, however, none cast blame upon the elder Babbs for having turned his wayward offspring out, even if it meant sending his mewling heir with her – especially as the girl refused to divulge the identity of her suitor.

When Blackhall had made inquiries as to how Silence, a farmer’s daughter largely marooned upon her father’s acreage, had managed to secretly bring the pregnancy to term under the eyes of the surrounding prattle-tongues, and her own kin, the usual answer was a change of topic to the impropriety of the infant’s constant posture at her breast.

Most were so concerned with the supposed vulgarity of this public nursing that they gave no notice to the vacant aspect about the new mother’s eyes. If she appeared haggard, it was the opinion of those who did observe her fatigue, that it was true of all recently-minted parents, and doubly so for those who set themselves to raise an innocent without a proper spouse.

Thomas had cursed the priggish nature of the area’s inhabitants as he’d run to retrieve his kit from the horse-shed for which he’d overpaid to shelter in.

The conversation that set him afoot was a short one.

“Sir,” Helen Brooks, Silence’s favoured companion, had said in interruption of his stroll upon a country lane. “I have risked much by making my way to you, so I would beg you hear me out. My brother has spoken of your unnatural gifts, and I ask you to consider the case of the youngest Babbs.”

“Speak on,” was Thomas’ reply.

The girl had collected herself then, slowing her speech so as to prevent the need for a repetition of her plea.

“If she was expectant, I would have known. We were neighbours, and the truest of confidants to each other. She’s barely whispered sweet words to a boy, so I do not see how it would be possible that she’s lain with a man.”

“You said ‘were’? Are you no longer acquainted?”

“That is the crux of why I have sought you out. Gardner – he who recommended you – has just now returned home from a stop at the inn, where, he reports, he witnessed her exodus in a northerly direction. He says that many laid unkind words at her feet, and that she was weeping into her chest as she departed with her charge at her teat. I know better, however, for I have seen them together. Silence’s head was stooped so that she might speak to her bundle, which, by itself, is not so unusual, but it – I have heard it speak back to her. I might say, more accurately, command her, though its mouth was gorging at her bosom.”

As he was familiar with tales of such a torment, Blackhall’s interrogations had been rapid and rough-tongued, but his rudeness made those he’d questioned eager to set him about his route. He’d quickly found the broken grass that marked her wake, but, as he enumerated Silence’s possible symptoms, he was disappointed to find all other inquires answered only with ignorance.

The length of the protracted pursuit had come as a surprise, but, on the fourth day, he’d grown confident that he’d overtake the girl by nightfall. It was then that he’d caught the first whiff of smoke on the wind.

* * *

Crushing the avaricious insect, Thomas felt a warm slick of his own vital fluids spread across his fingertips. His eyes had become keen, and he turned slow circles, hoping to catch sight of whatever puddle the pest originated from. He well knew that no such bloodsucker would be found far from water, and his survey was rewarded by a shimmer below two charred, cross-fallen, pines.

Knocking off his hat, Blackhall ran for the pool – spring or standing water, he cared not.

His headlong rush was brought up short by the withered husk of a corpse, once human, now nothing more than a tightly-drawn graying skin, set roughly over an assemblage of bones. She lay largely in the pool that was his destination, and it took only the briefest investigation to ascertain that it was Silence, as a disordered, three-deep row of puncture marks surrounded her right nipple on all sides.

Waving away the swarm of mosquitoes gathered over their birthing puddle, Thomas lay his hat upon her rigid face, and pledged to return for a proper burial.

Although he’d been delayed by the conflagration, his find gave him confidence that the matter would soon be resolved. Two ruts moved away from the cadaver, and through the ebony dust, illustrating clearly the path of the crawling brute.

It was a hard decision to still drink from the damp sepulcher, but he knew it would be little use if he were to perish of dehydration before he’d made some small vindication of the murder.

Another three hours found him standing over his objective.

“Beast,” he managed, kicking at the tiny form.

In defiance of the imp’s size, Blackhall found his foot rebuked as if by half the heft of a full grown man. The unexpected bulk further encouraged the frontiersman’s fury, however, and in short order Thomas had the fiend pinned beneath his sole, at the neck – as he might a snake.

The skin of camouflage that was the suckling’s greatest strength was rendered ineffective by the flexing rows of reed-like straws that made up the savage hellion’s mouth, and by a clear view of the split eyes that were so often hidden against the tender skin of its victim.

“Shall I be eternally assaulted by such as I have no recourse to end?” asked Thomas, addressing the sky. He faced his captive. “As you’ve none of the allergy to silver which besets so many of your occult brethren, I’ll only put a pause to your wickedness – but, with the honour of dearest love to bind me, I’ll find some way to dispatch you, no matter how long the work takes. To begin, I’ll render you feeble for as many decades as it’ll take you to regenerate your armament.”

With that, he dug into the layer of ash, and retrieved a fist-sized stone. The shattering of the counterfeit child’s hollow teeth took many hours, and the binding, and dual burials, took several more.

Flash Pulp is presented by http://skinner.fm, and is released under the Canadian Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 License.

Text and audio commentaries can be sent to skinner@skinner.fm, or the voicemail line at (206) 338-2792 – but be aware that it may appear in the FlashCast.

– and thanks to you, for reading. If you enjoyed the story, tell your friends.