Ghoulish Behaviour

I know I’ve touched on this topic before, but, please allow me to remind you of my concern that that we’re placing many of our eggs in one electronic basket, wrapped together tightly with fiber optic cable. I understand that we haven’t digitized all of our cultural output in its entirety, but we’re getting close.

I know I’ve touched on this topic before, but, please allow me to remind you of my concern that that we’re placing many of our eggs in one electronic basket, wrapped together tightly with fiber optic cable. I understand that we haven’t digitized all of our cultural output in its entirety, but we’re getting close.

My anxiety is for the delicacy of the medium – one misstep, and suddenly we’re back in 1933.

1933?

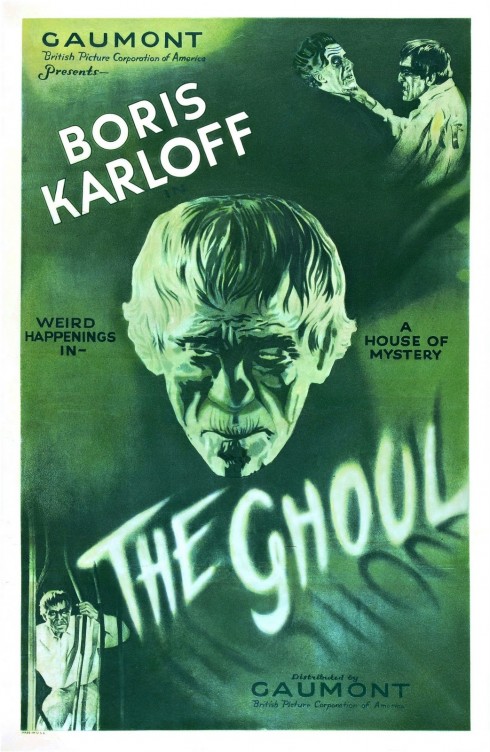

The Ghoul is a 1933 British Horror film […] was released in the US in January 1934 and reissued in 1938.

The movie is a historical landmark, as it was the first British horror “talkie“. It’s not a bad bit of film, although it has some comedic moments that seem strangely out of place.

What’s truly odd, however, is that I’ve seen it at all.

Subsequently it disappeared and was considered to be a lost film over the next 31 years.

Consider that The Ghoul was made after both Frankenstein and The Mummy – that Karloff was already famous, and was brought onto the project specifically for his notoriety. It may not stand against the quality of some of his other work, but, to my mind, this is as if we were to suddenly misplace every known copy of X-Men Origins: Wolverine.

In 1969, collector William K. Everson located a murky, virtually inaudible subtitled copy, Běs, behind the iron curtain in then-communist Czechoslovakia. Though missing eight minutes of footage including two violent murder scenes, it was thought to be the only copy left. Everson had a 16mm copy made and for years he showed it exclusively at film societies in England and the United States, memorably at The New School in New York City in 1975 on a Halloween triple bill of Lon Chaney in The Monster, Bela Lugosi in The Gorilla and Boris Karloff in The Ghoul. Subsequently, The Museum of Modern Art and Janus Film made an archival negative of that scruffy Prague print and it went into very limited commercial distribution.

Don’t get me wrong, I love volatile technologies – instability is often the sign of a burgeoning field of knowledge. My worry is only to ensure that not all of our cultural backup systems require a USB port.

There’s something to be said for redundancy.

Inadvertently in the early 1980s, a disused and forgotten film vault at Shepperton Studios, its door blocked by stacked lumber, was cleared and yielded [The Ghoul’s] dormant nitrate camera negative in perfect condition.

How do you just forget a film vault? I wonder what other films were in there as well?

As regards the electronic basket, the Internet Archive seems to share your concern. I read an article a few days ago saying they were planning to archive 10 million books – the old paper kind – to back up the digital versions.

http://www.wired.com/epicenter/2011/06/digital-books-on-paper/

And The Ghoul? Fun Karloff film for sure!

I have quite a lot of respect for the Internet Archive, and this article just adds to it.

“Digital archivists have long pointed out that given a sufficient length of time, data loss is a problem even for highly redundant, highly available, distributed storage systems.”

Which can be translated as “cracks still exist, and things keep slipping into them.”

Thanks for the link – although now I’ve got to consider how to find a modified 40′ shipping container, with a controllable environment, to store all of my Encyclopedia Brown books in.

Oh, another interesting bit of triva, (from http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0070917/trivia) although I can’t verify its truth:

“The negative and the outtakes [for 1973’s The Wicker Man] were stored at the vault in Shepperton studios. When it was bought, the new owner gave the order to clear the vault to get rid of all the old stuff. Foolishly, the vault manager put the negatives, which just arrived from the lab, with the ones which were to be destroyed.”

“but, to my mind, this is as if we were to suddenly misplace every known copy of X-Men Origins: Wolverine.”

And that would be bad because?

OK, a tad harsh, but it wasn’t that hot of a film.

Heh, I’m not saying it’d be a bad thing, just a mind-boggling one.