An Argument For The Undead

A while ago, fashion guru and fantastic lady, Jes Lacasse, was asking around regarding the staying power of the zombie genre, and I promised a post explaining why the shambling undead can still carry a story, despite their recent over-exposure.

A while ago, fashion guru and fantastic lady, Jes Lacasse, was asking around regarding the staying power of the zombie genre, and I promised a post explaining why the shambling undead can still carry a story, despite their recent over-exposure.

However, I must note that I’m no zombie academic – I’m just a life-long horror fan, and occasional writer of post-apocalyptic walking-rotter stories.

Before we can shoot straight to the dead folks, we’ve got to take a walk back in time.

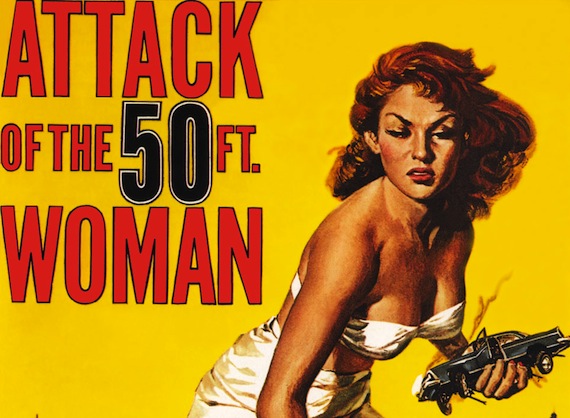

After the second world war, horror as a genre was right out. People had seen far too much killing in real life to want to head into a theater and watch some more, which is why most ’50s horror films are really science fiction thrillers revolving around either giant insects, (or, sometimes, people,) or aliens.

After the second world war, horror as a genre was right out. People had seen far too much killing in real life to want to head into a theater and watch some more, which is why most ’50s horror films are really science fiction thrillers revolving around either giant insects, (or, sometimes, people,) or aliens. This started to change as Vincent Price’s star began to rise, and as the British studio, Hammer Films, began to move away from science fiction and into scarier fare, but the genre as a whole didn’t really return in full force until the 1960s – just long enough for teenagers without combat experience to begin paying for their own theater admissions.

This started to change as Vincent Price’s star began to rise, and as the British studio, Hammer Films, began to move away from science fiction and into scarier fare, but the genre as a whole didn’t really return in full force until the 1960s – just long enough for teenagers without combat experience to begin paying for their own theater admissions.

I mention it because, in all eras, horror tends to be a reflection of the concerns of the period in which it is made. Worried about the advances in nuclear science? Make a giant bug movie. Concerned about our race to space? Bring on the aliens. Fretting about your child’s morality? Have their naughty behaviour cut short by an axe-wielding maniac.

No sub-genre is more complex in its presentation of these narratives than that of the reanimated corpse.

No sub-genre is more complex in its presentation of these narratives than that of the reanimated corpse.

The modern idea of zombies was defined in the late 1960s, amidst race riots, Vietnam, and white flight, and I’d be hard pressed to name another film that demonstrates that more clearly than the original Night Of The Living Dead, the progenitor of all modern shambler flicks.

Warning: here there be spoilers.

Night Of The Living Dead is really a movie about a black guy and a young woman taking the brunt of an unyielding invasion of aggression, while a rich white fellow hides his family in the basement, along with a couple of yokels – representing the working class – who kind of realize they should be helping the people upstairs, but are pretty comfortable just taking orders from the guy with the money. Eventually the lack of unity causes the whole situation to collapse.

Night Of The Living Dead is really a movie about a black guy and a young woman taking the brunt of an unyielding invasion of aggression, while a rich white fellow hides his family in the basement, along with a couple of yokels – representing the working class – who kind of realize they should be helping the people upstairs, but are pretty comfortable just taking orders from the guy with the money. Eventually the lack of unity causes the whole situation to collapse.

You don’t see that kind of commentary in a vampire film.

You don’t see that kind of commentary in a vampire film.

It isn’t just NOTLD either, it’s my contention that any zombie story can’t help but be a tale about society.

Dawn Of The Dead is a film about the vapid woes of consumerism, and Day Of The Dead actually probably failed under the weight of its science vs military/knowledge vs authority political message.

Even back so far as 1932’s White Zombie, the pattern holds: a white landholder in Haiti uses black zombie slaves to run his plantation, only to be stopped by a modern fellow who believes the situation unjust – well, and wants his girlfriend back.

Return Of The Living Dead is the reflection of the 1980s mentality that only the kids of the day knew what was going on, and that death can come cheap and easy in an age overshadowed with unstoppable (read: nuclear) annihilation.

The more modern Shaun Of The Dead, something of a comedy, is a tale about people expending their lives going to work, sitting around, drinking, and playing video games.

As a final example, Jonathan Coulton‘s song, Re: Your Brains, is a play on the vagaries of modern office life, small talk, and the types of requests we receive that are really demands.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cOlznuyPOeM]

I’ll stop there, but the pattern is endless, because zombies are the classic “they are us” enemy. The critical function of a zombie isn’t to be shot in the head, it’s to act as a crucible to force the leading characters into the hard decisions they avoid in their normal lives.

As a side note: this is also why I draw the line at fast zombies. Slow zombies force a mentality beyond just cheap scares. Something running at you fast can be anything – a dog, a dead guy, a four-hundred pound rabid orangutan – it’s the speed and mass that makes it scary, and the enforced space for a greater message is lost.

What I’m getting at is, the undead remain a strong contender in the pop culture space because there are as many variations in the significance of their situations as there are in the situations, big or small, that we face in our daily lives.

What I’m getting at is, the undead remain a strong contender in the pop culture space because there are as many variations in the significance of their situations as there are in the situations, big or small, that we face in our daily lives.

Fantastic post, and quite right.

I would like to add just a tiny bit about White Zombie,(things I am sure you know but left out in favor of brevity and staying on topic.)

White zombie is certainly, to an extent, a study in racism, but it more a study of the racism that exists within the broader context of imperialism and colonialism, as none of the white characters, Lugosi included, are natives of Haiti and all of them, the Governor, the wealthy young couple, even Lugosi, represent rich individuals and cultures from different nations and their views of and mistreatment toward the people of Haiti. In a sense, it is a small scale representation of what happened not just to the native Americans, but to all people who were (I refuse to say conquered) overwhelmed by a “superior” culture- for example, the native Pacific Islanders whose culture was wiped out by the Japanese. (And for “superior,” read “stronger.”) Just listen to the dialogue when the governor dismisses voodoo and other parts of Haitian culture. An interesting note is that the zombies of Lugosi’s sugar mill are a multi-ethnic bunch. What keeps them in common is that they are natives of Haiti- a “lesser” culture.

However, as a product of 1932, the producers were not going for any commentary or symbolism- it would be another 50 years or so before George Romero made anything like that explicit. It wasn’t even intended to be implicit- that was just how it was, how the attitudes were, no thought given to commentary.

So White Zombie works as a great reflection of the era, probably untainted by any deeper meaning by the producers but still full of deeper meaning. But the bottom line for me is that it is still in this era a moody, atmospheric, creepy film.

And one that was technically well made too. Never mind the special effects like the actors with the model castle shot in the background, or the insets and fades, but fior my money, the best shoot of the film is the tracking shot about (IIRC) 20 minutes in, as the camera follows a zombie as he walks through the sugar mill with a basket onhis head, dumps it into the grinder, losses his balance, and falls in as well. And then the camera continues to track past him. It is all so matter of fact, and not even a note of music in the scene.

This is a fantastic comment – I really have nothing more to add but a slow building clap.