True Pulp Tales

Before we begin, let me warn you: this post is not for the weak of heart.

Before we begin, let me warn you: this post is not for the weak of heart.

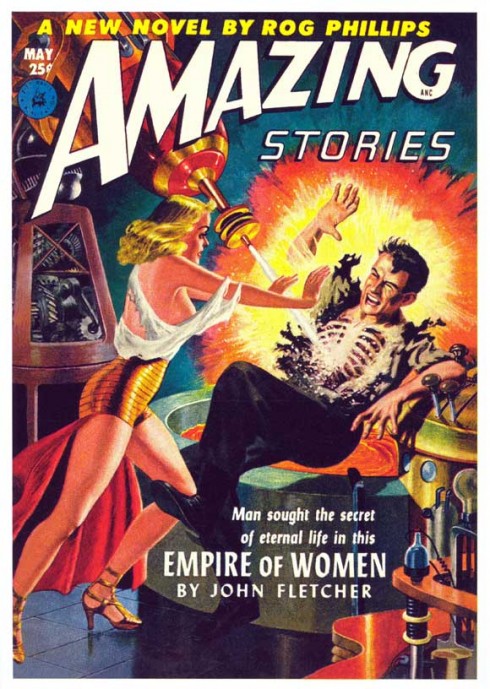

Yesterday, while exploring how pop fiction sometimes reinforces stereotypes, I was reminded of how often the world offers up scenarios too pulpy to seem true.

For example:

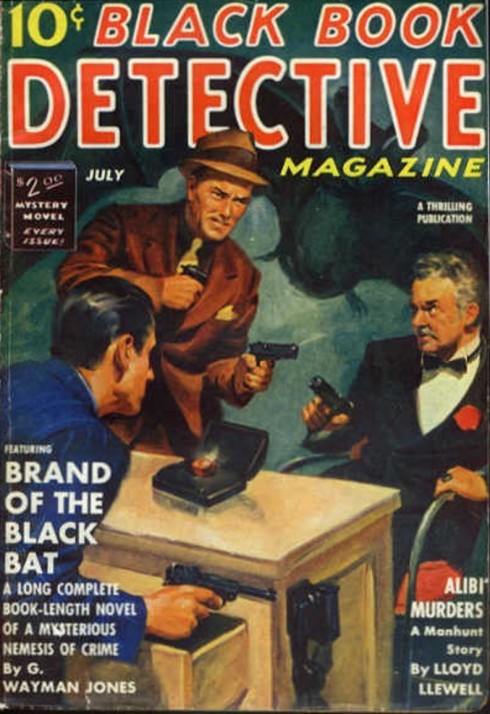

In 1969, [mob boss Vincent “Chin”] Gigante started feigning mental illness to escape criminal prosecution. He escaped conviction on bribery charges by producing a number of prominent psychiatrists who testified that he was legally insane. […] Almost every day he would return from his residence to his mother’s apartment at 225 Sullivan Street in Greenwich Village and emerge dressed in a bathrobe and pajamas or a windbreaker and shabby trousers. Accompanied by one or two bodyguards, he crossed the street to the Triangle Civic Improvement Association — a dingy storefront club that served as his headquarters — where he played pinochle and held whispered conversations with his associates.

If I were to write a gangster character like that, people would be shouting out the concluding twist before the end of the first act – and yet Gigante got away with it for twenty years.

It may be the case, however, that I’m simply too jaded.

“Nazi gold?” I might say to myself, “one of the most hackneyed plot devices you’ll ever encounter – there’s certainly nothing more to be said on the topic, and no telling, however true, would amaze me.”

– but I’d be wrong.

When Germany invaded Denmark in World War II, the Hungarian chemist George de Hevesy dissolved the gold Nobel Prizes of the German physicists Max von Laue (1914) and James Franck (1925) in aqua regia to prevent the Nazis from confiscating them. […] De Hevesy placed the resulting solution on a shelf in his laboratory at the Niels Bohr Institute. It was subsequently ignored by the Nazis who thought the jar—one of perhaps hundreds on the shelving—contained common chemicals. After the war, de Hevesy returned to find the solution undisturbed and precipitated the gold out of the acid. The gold was returned to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Nobel Foundation who recast the medals and again presented them to Laue and Franck.

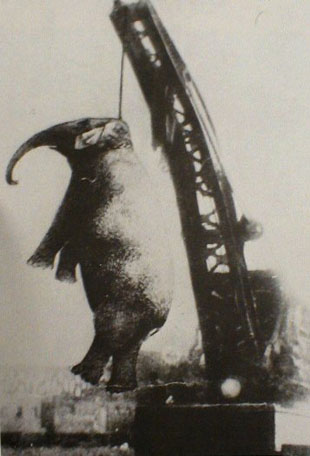

As mind-blowing as both of those stories are, however, they don’t quite top the amazement I felt when I heard the true crime tale of Murderous Mary.

On September 11, 1916, a hotel worker named Red Eldridge […] was killed by Mary in Kingsport, Tennessee […] within minutes, a local blacksmith tried to kill Mary, firing more than two dozen rounds with little effect […] Charlie Sparks, reluctantly decided that the only way to quickly resolve the potentially ruinous situation was to kill the [circus] elephant in public.

Bullets having had little effect, and poison/electricity being in too short supply to complete the task, they turned to justice’s ancient friend, the hangman’s rope – frankly, I wouldn’t believe it if I hadn’t seen the proof:

On last night’s FlashCast we spent some time discussing the nature of pulp, and its effect on the real world. It’s easy to think of pop culture as disposable, but we often miss how it can influence our own thinking.

On last night’s FlashCast we spent some time discussing the nature of pulp, and its effect on the real world. It’s easy to think of pop culture as disposable, but we often miss how it can influence our own thinking.

My cranium has found itself trapped in Scripts-ville, so I apologize for the sporadic posting that is sure to follow in my wake.

My cranium has found itself trapped in Scripts-ville, so I apologize for the sporadic posting that is sure to follow in my wake.

My love of Boston Dynamics’ robotic cargo-carrier, Big Dog, is

My love of Boston Dynamics’ robotic cargo-carrier, Big Dog, is

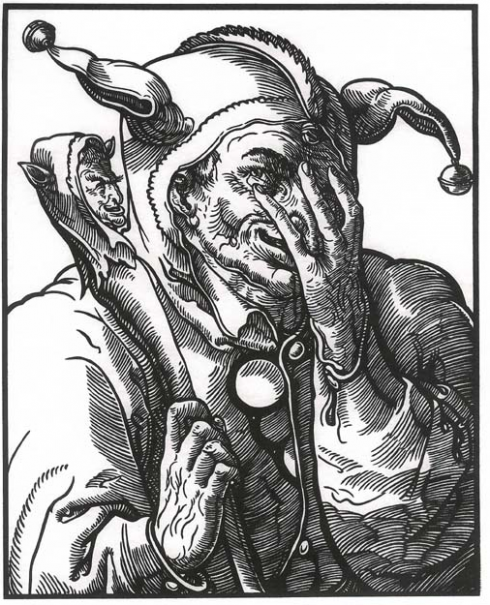

Many historians claim the character died out with the decline of royal courts, but, it’s my contention that, despite his modernization, the buffoon survives. In fact, I’ll go a step further and argue that any political structure, even if the politics are personal, will breed a place for the role.

Many historians claim the character died out with the decline of royal courts, but, it’s my contention that, despite his modernization, the buffoon survives. In fact, I’ll go a step further and argue that any political structure, even if the politics are personal, will breed a place for the role.

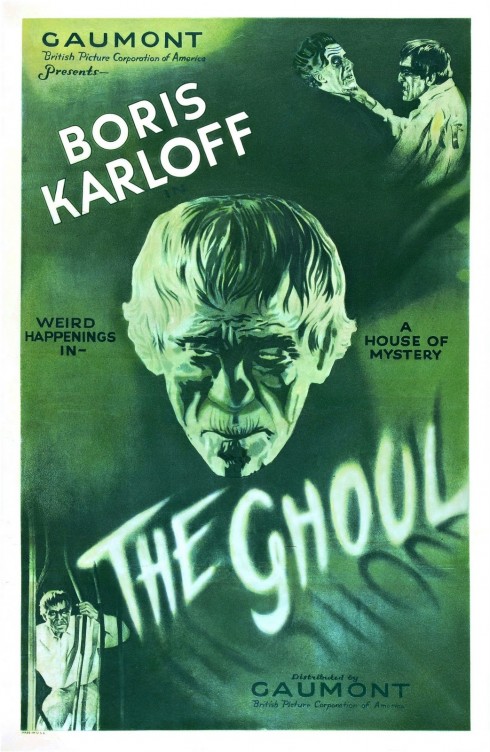

I don’t deal well with the last image of my day being Peter Lorre, dressed as a hobo-clown, slinking around in a filthy bathrobe.

I don’t deal well with the last image of my day being Peter Lorre, dressed as a hobo-clown, slinking around in a filthy bathrobe.