A while ago, fashion guru and fantastic lady, Jes Lacasse, was asking around regarding the staying power of the zombie genre, and I promised a post explaining why the shambling undead can still carry a story, despite their recent over-exposure.

A while ago, fashion guru and fantastic lady, Jes Lacasse, was asking around regarding the staying power of the zombie genre, and I promised a post explaining why the shambling undead can still carry a story, despite their recent over-exposure.

However, I must note that I’m no zombie academic – I’m just a life-long horror fan, and occasional writer of post-apocalyptic walking-rotter stories.

Before we can shoot straight to the dead folks, we’ve got to take a walk back in time.

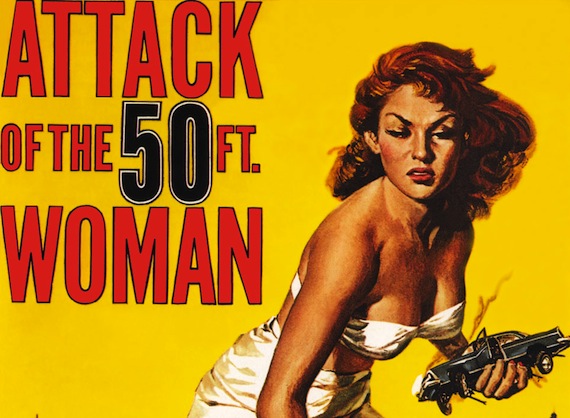

After the second world war, horror as a genre was right out. People had seen far too much killing in real life to want to head into a theater and watch some more, which is why most ’50s horror films are really science fiction thrillers revolving around either giant insects, (or, sometimes, people,) or aliens.

After the second world war, horror as a genre was right out. People had seen far too much killing in real life to want to head into a theater and watch some more, which is why most ’50s horror films are really science fiction thrillers revolving around either giant insects, (or, sometimes, people,) or aliens. This started to change as Vincent Price’s star began to rise, and as the British studio, Hammer Films, began to move away from science fiction and into scarier fare, but the genre as a whole didn’t really return in full force until the 1960s – just long enough for teenagers without combat experience to begin paying for their own theater admissions.

This started to change as Vincent Price’s star began to rise, and as the British studio, Hammer Films, began to move away from science fiction and into scarier fare, but the genre as a whole didn’t really return in full force until the 1960s – just long enough for teenagers without combat experience to begin paying for their own theater admissions.

I mention it because, in all eras, horror tends to be a reflection of the concerns of the period in which it is made. Worried about the advances in nuclear science? Make a giant bug movie. Concerned about our race to space? Bring on the aliens. Fretting about your child’s morality? Have their naughty behaviour cut short by an axe-wielding maniac.

No sub-genre is more complex in its presentation of these narratives than that of the reanimated corpse.

No sub-genre is more complex in its presentation of these narratives than that of the reanimated corpse.

The modern idea of zombies was defined in the late 1960s, amidst race riots, Vietnam, and white flight, and I’d be hard pressed to name another film that demonstrates that more clearly than the original Night Of The Living Dead, the progenitor of all modern shambler flicks.

Warning: here there be spoilers.

Night Of The Living Dead is really a movie about a black guy and a young woman taking the brunt of an unyielding invasion of aggression, while a rich white fellow hides his family in the basement, along with a couple of yokels – representing the working class – who kind of realize they should be helping the people upstairs, but are pretty comfortable just taking orders from the guy with the money. Eventually the lack of unity causes the whole situation to collapse.

Night Of The Living Dead is really a movie about a black guy and a young woman taking the brunt of an unyielding invasion of aggression, while a rich white fellow hides his family in the basement, along with a couple of yokels – representing the working class – who kind of realize they should be helping the people upstairs, but are pretty comfortable just taking orders from the guy with the money. Eventually the lack of unity causes the whole situation to collapse.

You don’t see that kind of commentary in a vampire film.

You don’t see that kind of commentary in a vampire film.

It isn’t just NOTLD either, it’s my contention that any zombie story can’t help but be a tale about society.

Dawn Of The Dead is a film about the vapid woes of consumerism, and Day Of The Dead actually probably failed under the weight of its science vs military/knowledge vs authority political message.

Even back so far as 1932’s White Zombie, the pattern holds: a white landholder in Haiti uses black zombie slaves to run his plantation, only to be stopped by a modern fellow who believes the situation unjust – well, and wants his girlfriend back.

Return Of The Living Dead is the reflection of the 1980s mentality that only the kids of the day knew what was going on, and that death can come cheap and easy in an age overshadowed with unstoppable (read: nuclear) annihilation.

The more modern Shaun Of The Dead, something of a comedy, is a tale about people expending their lives going to work, sitting around, drinking, and playing video games.

As a final example, Jonathan Coulton‘s song, Re: Your Brains, is a play on the vagaries of modern office life, small talk, and the types of requests we receive that are really demands.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cOlznuyPOeM]

I’ll stop there, but the pattern is endless, because zombies are the classic “they are us” enemy. The critical function of a zombie isn’t to be shot in the head, it’s to act as a crucible to force the leading characters into the hard decisions they avoid in their normal lives.

As a side note: this is also why I draw the line at fast zombies. Slow zombies force a mentality beyond just cheap scares. Something running at you fast can be anything – a dog, a dead guy, a four-hundred pound rabid orangutan – it’s the speed and mass that makes it scary, and the enforced space for a greater message is lost.

What I’m getting at is, the undead remain a strong contender in the pop culture space because there are as many variations in the significance of their situations as there are in the situations, big or small, that we face in our daily lives.

What I’m getting at is, the undead remain a strong contender in the pop culture space because there are as many variations in the significance of their situations as there are in the situations, big or small, that we face in our daily lives.

I just wanted to follow up the last Blackhall with a quick note about the reality of the unpleasant situation in question.

I just wanted to follow up the last Blackhall with a quick note about the reality of the unpleasant situation in question. A few country blocks from our old house, there was a large sign set at the edge of some entrepreneur’s lawn. The beast was made of spray paint and plywood, and proudly announced that “We Cuts Grass” – I wouldn’t hire them, either.

A few country blocks from our old house, there was a large sign set at the edge of some entrepreneur’s lawn. The beast was made of spray paint and plywood, and proudly announced that “We Cuts Grass” – I wouldn’t hire them, either. Hey, remember those crazy cultists from The Temple Of Doom, the ones who lived in a mine somehow secretly attached to the royal palace?

Hey, remember those crazy cultists from The Temple Of Doom, the ones who lived in a mine somehow secretly attached to the royal palace?

A while ago, fashion guru and fantastic lady,

A while ago, fashion guru and fantastic lady,  After the second world war, horror as a genre was right out. People had seen far too much killing in real life to want to head into a theater and watch some more, which is why most ’50s horror films are really science fiction thrillers revolving around either giant insects, (or, sometimes, people,) or aliens.

After the second world war, horror as a genre was right out. People had seen far too much killing in real life to want to head into a theater and watch some more, which is why most ’50s horror films are really science fiction thrillers revolving around either giant insects, (or, sometimes, people,) or aliens. This started to change as Vincent Price’s star began to rise, and as the British studio, Hammer Films, began to move away from science fiction and into scarier fare, but the genre as a whole didn’t really return in full force until the 1960s – just long enough for teenagers without combat experience to begin paying for their own theater admissions.

This started to change as Vincent Price’s star began to rise, and as the British studio, Hammer Films, began to move away from science fiction and into scarier fare, but the genre as a whole didn’t really return in full force until the 1960s – just long enough for teenagers without combat experience to begin paying for their own theater admissions. No sub-genre is more complex in its presentation of these narratives than that of the reanimated corpse.

No sub-genre is more complex in its presentation of these narratives than that of the reanimated corpse. Night Of The Living Dead is really a movie about a black guy and a young woman taking the brunt of an unyielding invasion of aggression, while a rich white fellow hides his family in the basement, along with a couple of yokels – representing the working class – who kind of realize they should be helping the people upstairs, but are pretty comfortable just taking orders from the guy with the money. Eventually the lack of unity causes the whole situation to collapse.

Night Of The Living Dead is really a movie about a black guy and a young woman taking the brunt of an unyielding invasion of aggression, while a rich white fellow hides his family in the basement, along with a couple of yokels – representing the working class – who kind of realize they should be helping the people upstairs, but are pretty comfortable just taking orders from the guy with the money. Eventually the lack of unity causes the whole situation to collapse. You don’t see that kind of commentary in a vampire film.

You don’t see that kind of commentary in a vampire film.

What I’m getting at is, the undead remain a strong contender in the pop culture space because there are as many variations in the significance of their situations as there are in the situations, big or small, that we face in our daily lives.

What I’m getting at is, the undead remain a strong contender in the pop culture space because there are as many variations in the significance of their situations as there are in the situations, big or small, that we face in our daily lives. I must admit, rather shamefacedly, that I hadn’t realized that elevenses was actually a real thing. I think the concept of tea time is globally acknowledged, but the tradition of a morning snack somehow escaped my notice.

I must admit, rather shamefacedly, that I hadn’t realized that elevenses was actually a real thing. I think the concept of tea time is globally acknowledged, but the tradition of a morning snack somehow escaped my notice.

CNN has a

CNN has a  My understanding is that the giants were herbivorous foragers that dug through the snow to locate plant material to munch on – if we let them roam during our non-ice age, will they overeat?

My understanding is that the giants were herbivorous foragers that dug through the snow to locate plant material to munch on – if we let them roam during our non-ice age, will they overeat?

It may not be humorous, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a ridiculous question. Here’s a quote from Jared Loughner, which I recently came across over at

It may not be humorous, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a ridiculous question. Here’s a quote from Jared Loughner, which I recently came across over at  I was stumbling around wikipedia, doing some research, and I came across an article entitled “

I was stumbling around wikipedia, doing some research, and I came across an article entitled “ I do love the mental image of squirrels with tiny satellite dishes strapped to their backs and secret service-style earpieces equipped, but, again, I rather suspect this is a bit of a case of mistaken science identity, probably related to migration. Even in this day and age, enforced ignorance of what’s actually possible can put people into the realm of Clarke’s third law.

I do love the mental image of squirrels with tiny satellite dishes strapped to their backs and secret service-style earpieces equipped, but, again, I rather suspect this is a bit of a case of mistaken science identity, probably related to migration. Even in this day and age, enforced ignorance of what’s actually possible can put people into the realm of Clarke’s third law.